Ducking Autocorrect

Gideon Lewis-Kraus writing at Wired on the History of Autocorrect:

Given how successful autocorrect is, how indispensable it has become, why do we stay so fixated on the errors? It's not just because they represent unsolicited intrusions of nonsense into our glassy corporate memoranda. It goes beyond that. The possibility of linguistic communication is grounded in the fact of what some philosophers of language have called the principle of charity: The first step in a successful interpretation of an utterance is the belief that it somehow accords with the universe as we understand it. This means that we have a propensity to take a sort of ownership over even our errors, hoping for the possibility of meaning in even the most perverse string of letters. We feel honored to have a companion like autocorrect who trusts that, despite surface clumsiness or nonsense, inside us always smiles an articulate truth.

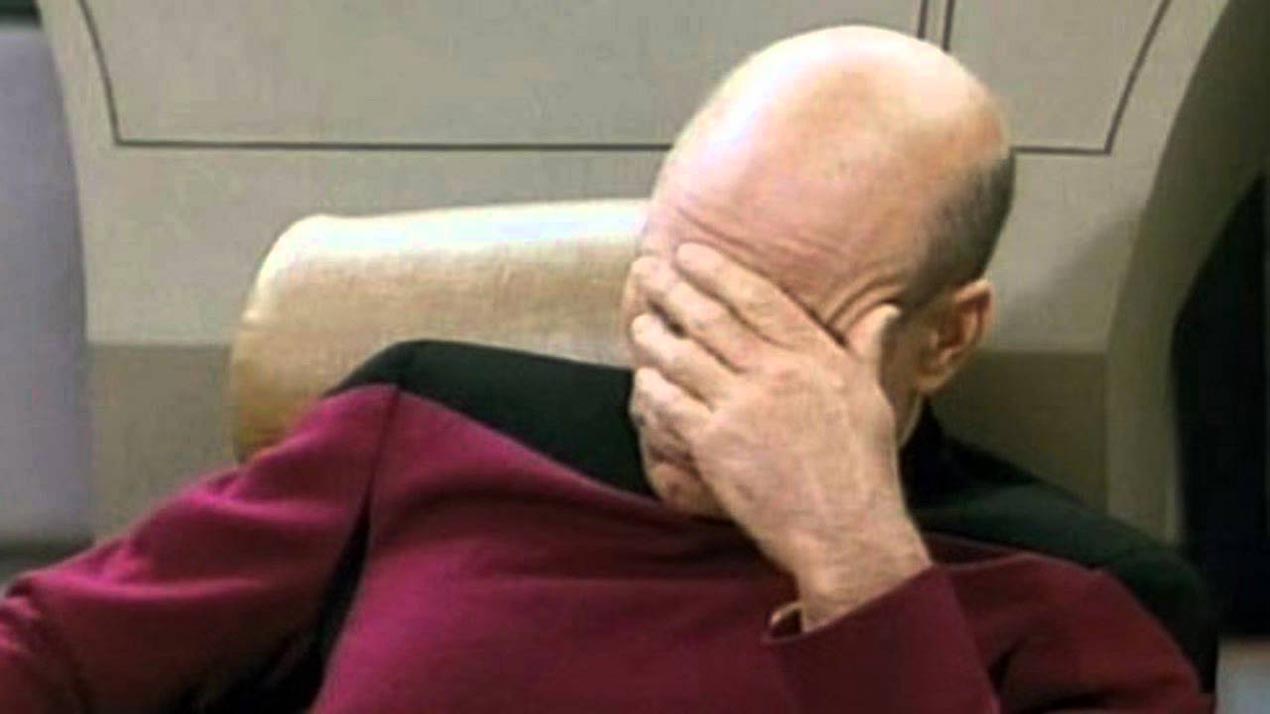

I've been fascinated by Autocorrect since I purchased my first iPhone in 2008. While I had used it for many years before that, it only became amusing once the feature made its way to the phone. For the first time, this article made me question why it took so long to become funny to me. I think I've got an answer.

While I've always been a fan of technology, no piece of technology had ever been as surprisingly useful and thus, me so surprisingly attached to it. Its been said many times that smartphones are the first truly personal computer and I agree.

We laugh at the crazy responses Siri gives us, both intentional and unintentional. This little slab of glass, metal and plastic we carry around in our pockets is our charm against boredom, our method of settling disputes and our tether to the rest of the world. When this device that means and does so much for us does something unexpected, then we tend to ascribe something more than just a random miscalculation. It takes on meaning, even if that meaning is mostly just humor.